Does New Zealand’s economy even need coal?

A fuel with a whiff of smoke-filled Victorian London seems a touch outdated in a country that trades on a clean green brand.

In reality, coal’s not a big source of energy in New Zealand – it’s just an important one.

In New Zealand, coal accounts for 7% of our total energy supply[1]. In the United States it’s 12% [2] , the European Union 14% [3] , and Australia 31% [5] .

Seven percent might not sound much, but if we take a look at who’s using coal in New Zealand, and why they haven’t stopped already, it’s clear it’s not easy to put our coal consumption on the back burner anytime soon.

Earning a crust from exporting food

The combined value of New Zealand’s food exports is more than most people would find down the back of the couch – dairy and meat brought about $25 billion dollars into New Zealand in 2020 – and then yeah, fruit and seafood a bit over $5 billion.

Getting all that milk and meat ready to ship offshore in exchange for $25,000,000,000[5] takes a lot of energy, and a lot of that comes from fossil fuels.

Dairy

Starting with the big cheese (or sack of milk powder), all those dairy exports – whether milk powder, cheese, butter, milk, yoghurt bring in more than $17,000,000,000 in export earnings[6]. Producing them directly employs tens of thousands of New Zealanders from dairy farm to dairy factory.

The sector’s use of coal – close to 700,000 tonnes per year[7] – gets a bit of heat. It’s not the only source of energy in dairy manufacturing, but it is the largest, supplying just over half of dairy processing’s energy needs [8] .

Fonterra

Fonterra’s aim is to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, and that means reducing its coal consumption – no mean feat given it’s the cooperative’s largest source of energy[9].

The Climate Change Commission recommended an end coal use in food production by 2037 – a recommendation Fonterra called “ambitious”.

While only eight of Fonterra’s 29 sites around New Zealand use coal, those sites use an awful lot of coal, meaning the fuel makes up 39%[10] of energy used to process milk.

Taking the largest slice out of the energy pie would mean another energy source would have to make the cut.

To date, only one of Fonterra’s sites that was using coal has stopped doing so – Te Awamutu, a factory in the central North Island that previously made up 10% of the company’s coal use. This factory happens to be in the central North Island, an area with abundant wood residues, and cheap waste geothermal heat to dry that wood into low moisture, high energy pellets.

This alignment of the stars has allowed this one site to stop using coal.

One plant near Nelson, Brightwater, blends waste wood with coal, but coal still accounts for about 75% of the energy at the site which, in itself, is a mere 1.6% of the cooperative’s South Island energy consumption.

Fonterra looked at electrifying its largest South Island factory, Edendale, in Southland, but found the total cost of running the site (not just the energy costs) would have increased by 50% and required lines upgrades of $160,000,000[11].

Winding down the voltage, the cooperative then looked at electrifying its second smallest South Island site, Stirling, an Otago cheese factory. Cheese production requires much less energy than drying milk powder and other products, so Fonterra thought electric cheese might be worth a crack.

Fonterra found even the cost of electrifying a small cheese plant was a bit of a shock. Fonterra has since ruled out switching to electricity for any of its boilers[12], due to the cost of installation, and the increase in running costs they would cause due to electricity being about 3-4 times the cost of coal. Emissions would have been lower, but the cost was simply too high.

What about wood?

Fonterra has since made plans to switch its Stirling site to wood chips, but there’s only so much wood to go around. Conversions of bigger, more energy hungry sites won’t be so simple. Obstacles include wood supply – the majority of Fonterra’s coal use is in the South Island, and 72.5% of New Zealand’s pine plantations are in the North Island[13] – about 33% in the Central North Island alone. Carting wood fuels such long distances isn’t considered economic.

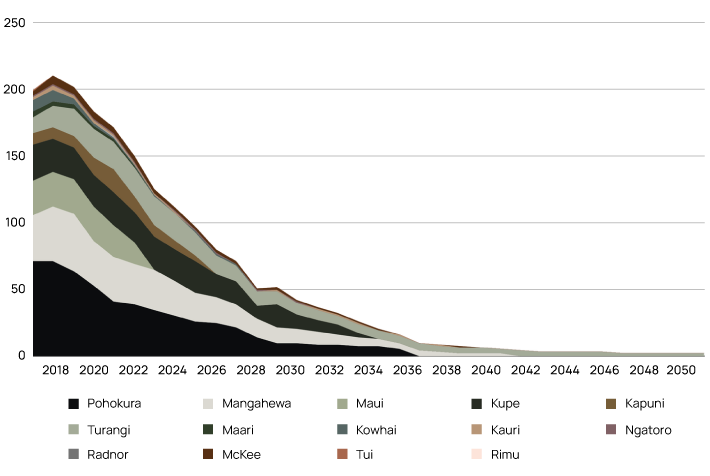

Natural gas?

For each unit of energy produced, natural gas emits about half as much carbon dioxide as coal. While natural gas provides three quarters of the energy consumed by dairy manufacturers in the North Island[14], it’s not an option in the South Island.

Fonterra said in its submission to the Climate Change Commission that a compromised gas supply would inhibit the transition off coal by 2037. If Fonterra doesn’t have a secure supply of gas, it has said it may need to switch its gas boilers to renewable alternatives sooner than 2037. Given gas production in New Zealand is forecast to fall 50-75% in the coming 15 years[15], Fonterra may well be trying to transition from gas much earlier than coal if it wants to keep processing milk in the North Island.

Gas production profile (forecast) to 2050

(petajoules)

Red meat

Red meat accounts for about $8,000,000,000 of export earnings[16], and 35,000 direct jobs across its farming and processing operations[17].

In all, about a third of the energy used at freezing works around New Zealand comes from coal, with the majority of the remainder coming from natural gas[18].

In 2020, that amounted to about 95,000[19] tonnes – 80% of which was likely consumed in the South Island.

This coal and gas is used at the places where sheep and cattle go in one end and vacuum packed ribeye steak, lamb chops, and mince meats come out the other.

Most meat companies are working to find an alternative to coal – it’s just not easy. The Meat Industry Association (representing 99% of the sector) has told the government the solution will likely end up being some mix of electric heat pumps and burning wood but said the conversion will be an “enormous challenge”[20], and potentially “an excessive burden on an industry already facing significant headwinds”[21].

Meat processor and exporter, ANZCO, told the government last year the cost of converting its coal boilers to electric boilers would require an investment of $41,300,000, plus another $9,500,000 for power infrastructure upgrades[22].

But that’s just the installation – ANZCO estimates its annual energy bill (which at present makes up 20% of its costs) would go from $5.32 million a year to $16.5 million dollars a year – an increase of 210%[23].

Options for wood conversion for the company are also limited – its three coal boilers are located in areas of the country with the lowest pine forest cover.

The Meat Industry Association has said conversions from coal to renewables will be a matter for individual companies based on the availability of wood waste and local electricity network around each plant.

Silver Fern Farms, New Zealand’s largest meat processor, has received government subsidies to cover half the $7.6 million cost of installing heat pumps at plants in Christchurch and Balclutha, which will allow the company to halve its coal use by 2023, reduce it by two thirds by 2025, and end coal use entirely by 2030. Its chief executive has said if it were purely a financial decision, the company “would be delaying for much longer, but we feel as though it is the right thing to do”[24].

In an industry where processors run profits anywhere between half a percent to three percent in any given year, if not losses, any additional costs can have a strain on the industry’s viability.

A material world

You’d be hard pressed to go anywhere in New Zealand and not see some steel or concrete. Whether you’re crossing the Auckland Harbour bridge in rush hour or staring down a gorge in the back country on a bridge of steel rope and wire bolted into concrete foundations, it’s pretty much everywhere.

And although steel and cement require a fair bit of coal to produce, they’re also vital for building things that reduce CO2 emissions – wind turbines, hydro electricity and geothermal plants, high rise buildings in denser cities where people get around on steel trains and buses on steel tracks, powerlines to get all that clean electricity to electrified transport.

Then there’s other nice to haves like houses, highways, and footpaths – the average new house, for example, requires about 2.7 tonnes of steel[25].

The question for New Zealand is whether, or to what extent, we wish to produce steel and cement and create jobs here while having full control over the environmental and health and safety standards or whether we’re happy to leave that to other countries to worry about.

New Zealand steel production

New Zealand produces about 650,000 tonnes of steel a year[26] – in doing so burning about 800,000 tonnes of coal[27]. We import steel as well, not just in its raw form but in products like second-hand Toyotas from Japan and can openers from China.

But domestic steel production has its advantages, like 1,400 highly paid jobs at NZ Steel’s Glenbrook mill[28] in South Auckland.

According to the company, for every $100 spent on domestically produced steel, $80 remains in the New Zealand economy – versus merely $5 when steel is imported[29].

Beyond those benefits, having steel that can be produced domestically means we can get steel at short notice – about five times faster than if sourcing steel from offshore.

In 2020, when a section of the Auckland Harbour Bridge was badly damaged, the necessary parts were produced, and complex repairs completed in three weeks. This could have taken eleven weeks if imported product had to be sourced and shipped here[30].

NZ Steel has raised concerns over the cost of business in New Zealand as a result of government climate policies like the emissions trading scheme, and electricity prices.

The company says most of its emissions come from its use of coal, which is the only viable source of carbon in the production of steel[31] – an ingredient for a chemical process, more so than a source of energy.

One option is for the company to continue operating in New Zealand and push for lower costs, but if it becomes economically unviable due to costs imposed it would have to plan for closing down its New Zealand business[32].

While NZ Steel’s production costs are impacted by climate change measures like the New Zealand Emissions Trading scheme, imported steel from other countries is not.

As of April 2021, about 22% of all global greenhouse gas emissions are covered by some form of price on carbon[33] , with the average price per tonne of CO2 emitted about $3.00 USD[34] – in New Zealand, the price was $26.00 USD, but it has since risen.

Cement production

While a different product and process, cement (used to make concrete) is used in many of the same instances as steel.

The foundations on which the kiwi dream of homeownership are built, the footpaths along which our children walk to school, foundations for wind turbines and the material used for hydro and geothermal electricity, all rest firmly on concrete, a mixture of gravel, water, and cement.

About 60% of the cement supply in New Zealand is sourced from one New Zealand producer, Golden Bay Cement[35]. The remainder of New Zealand’s supply is sourced from offshore. Cement produced in New Zealand has a carbon footprint about 20% lower than that sourced from offshore[36].

While coal is a major ingredient and energy source in cement manufacturing worldwide, New Zealand’s sole manufacturer, Golden Bay Cement, has increasingly substituted its manufacturing with biomass and, more recently, shredded waste tyres[37].

This can reduce but not eliminate the reliance New Zealand’s sole cement producer has on coal, at least not in the near future.

Coal will remain a vital part of ensuring production continues to be viable in New Zealand, which is important, unless we’re happy to see job losses domestically, which will lead to a greater reliance on an imported, more carbon intensive supply of cement.

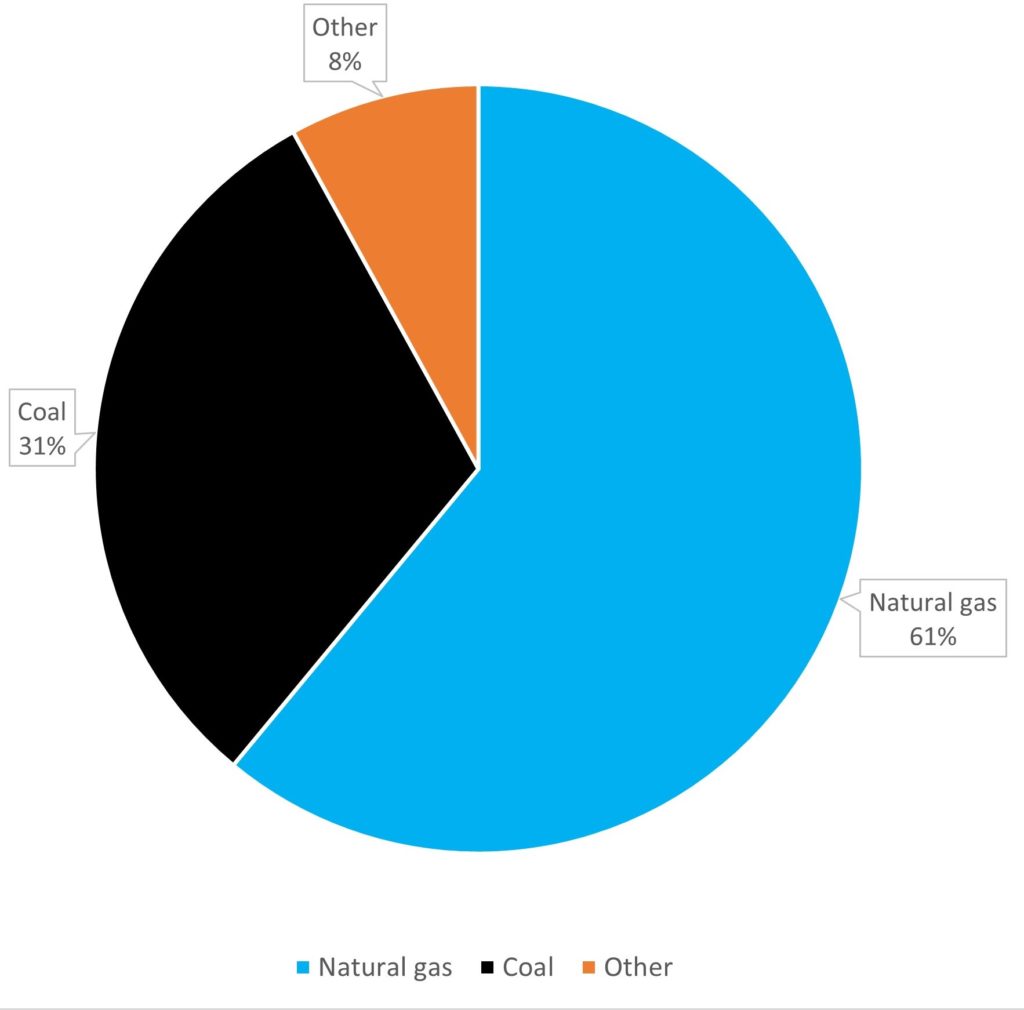

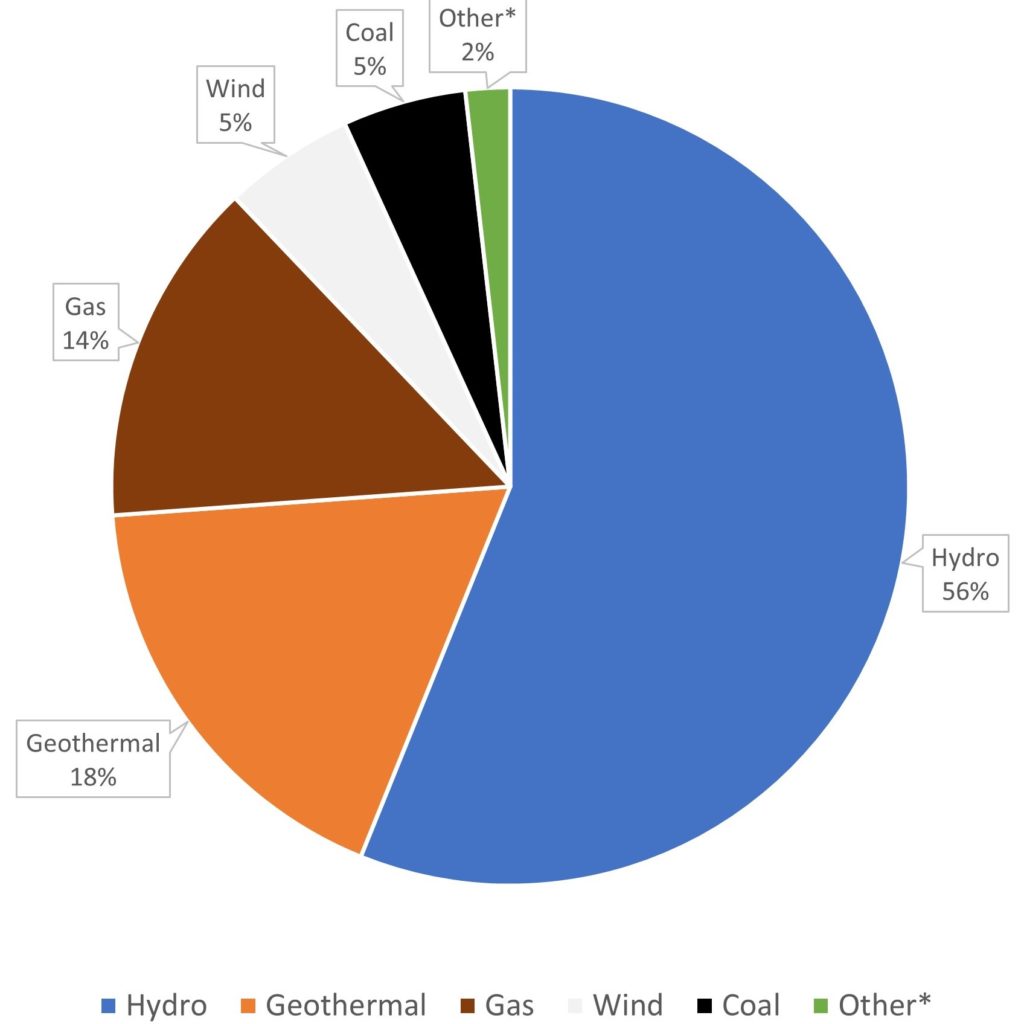

Electricity

From electric cars to electric toothbrushes, electricity is likely to play a larger role in New Zealand in the coming decades. Key to this will be ensuring New Zealand has a secure supply of electricity.

New Zealand’s renewable electricity (4th highest proportion of renewable electricity in the world) means on average our electricity comes from 80% renewable resources, but the gap between electricity supply and electricity demand can be a hard gap to close.

The government has made a commitment to get New Zealand’s electricity supply to 100% renewable by 2030. Ensuring that will be 100% reliable 100% of the time remains a challenge.

Coal and natural gas provide much needed backup for the grid when extra demand requires it. Some years, like 2016, fossil fuels account for only 15% of our electricity supply, but other years, like 2020, it’s closer to 20%[38].

Without capacity to draw on coal and natural gas for extra electricity generation when renewables like water and wind don’t play ball, electricity supply can be compromised. This was illustrated in August 2021[39], when power was cut across some areas of the country.

With a push to electrify industry and transport, and to also maintain current security of supply, it’s vital New Zealand’s generation can keep up with increases in demand for electricity when they occur.

New Zealand electricity generation by source 2020

A New Zealand economy without coal?

If New Zealand were to stop using coal tomorrow, our ability to feed ourselves and export food to the world would come under serious pressure. Our ability to produce our own steel and cement would simply be lost.

Our electricity supply would be intermittent, and subject to the weather patterns of renewables that depend largely on rain and wind.

There’s not a single coal user – food producers, Genesis Energy, NZ Steel, Golden Bay Cement – that hasn’t committed to reducing if not eliminating their coal use as soon as they can afford to do so.

Some are already taking steps – Golden Bay Cement’s use of wood and shredded tyres to reduce the coal needed to produce cement, Fonterra throwing millions of dollars at feasibility studies, and some meat companies and tomato growers are converting at least some of their operations to cleaner energy sources.

Setting arbitrary dates by which coal use should end will have questionable impact on global emission (any industrial activity that reduces or stops here is likely to increase abroad) but a certain and severe impact on New Zealand’s economy. If the companies haven’t found an alternative by then, they’ll go bust, and if they have found something, they won’t need to be forced to use it – they’ll rush to it and be sending out tweets, Facebook posts, and press releases faster than you can say zero emissions.

A premature end to the availability of an energy source that supports such large and important parts of our economy and way of life in the absence of technically or economically viable alternatives would be devastating.

That this devastation would reduce New Zealand’s emissions by about seven or eight percent (some of which would likely end up occurring offshore as other economies step in to meet demand for goods New Zealand currently produces) means it is worth at least asking whether that price is worth paying, or whether systems like having a price on emissions and allowing businesses to decide the most cost-effective way for emissions to be reduced would allow for smoother and more just transition.

If a just transition is not achieved, New Zealand’s food production, supply of domestically produced critical materials such as steel and cement, and our electricity supply could all be compromised.

References

View the economy references page here.