New Zealand’s industrial sector uses a lot of coal and gas – process heat emissions account for about 8% of New Zealand’s carbon dioxide emissions[1].

In addition to its role in providing energy to factories, coal is used as a source of carbon in steel production, and in electricity generation.

While using electricity isn’t viable when making steel from raw materials, and using electricity to generate electricity is wishful thinking, using electricity instead of coal or gas for drying milk powder or heating water for freezing works and hothouses has been suggested to reduce New Zealand’s industrial emissions.

Electricity already being used

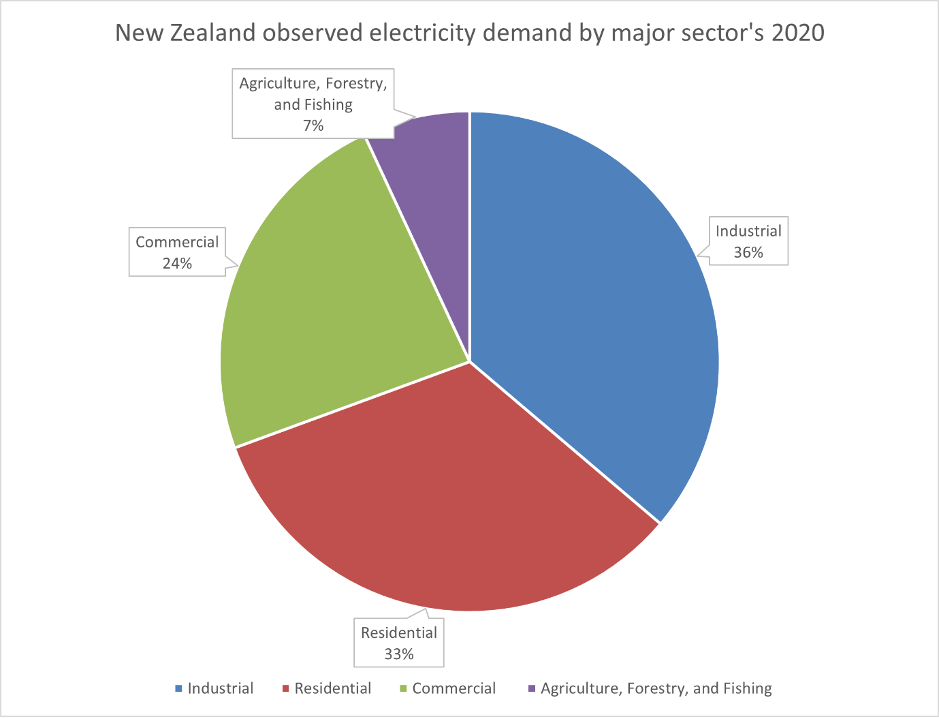

By sector, industry is already a large electricity consumer of New Zealand’s existing electricity supply – in fact it’s the largest[2], although a third of this is consumed by Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter (which consumes about 13% of New Zealand’s electricity[3]).

The below graph[4] gives a breakdown of the percentage of demand from each sector in New Zealand in the 2020 year – transport and onsite consumption, which amount to about 1.7% are not included in the chart.

Increasing electricity’s role in industry

The Climate Change Commission says electricity is about 3-5 times[5] the cost of coal or natural gas for industrial energy users under current carbon prices. This means electrification can come at a significant cost to factories if they decide to stop using fossil fuels in favour of electricity.

If New Zealand’s large energy users were to convert to electricity, New Zealand’s combined electricity generation and distribution would have to increase to keep up with the increased demand – and that’s before people even plug in their electric vehicles.

What’s the cost of electrification?

Those in the business of processing dairy products, turning livestock into 500 gram servings of meat, growing vegetables, and producing steel and cement rely heavily on coal or natural gas, or both.

This makes the cost of electrifying prohibitive for most large industrial users in New Zealand.

Are New Zealand companies electrifying already?

To a limited extent, yes. In 2019 dairy company, Synlait, installed an electrode boiler at its Dunsandel site in Canterbury[6]. It should be noted this electrode boiler comes in addition to three coal boilers and has not served to replace coal use at the site.

The boiler has a 6 megawatt capacity, serving in addition to the existing coal capacity of 75 megawatts[7].

So, while the electrode boiler capacity may have served to ensure no additional coal capacity was needed, it would be a stretch to say it has displaced any existing coal use.

At the time of installation, it was estimated to have twice the operating costs as a coal equivalent over a ten year period[8].

Another dairy processor, Open Country Dairy, has installed an electrode boiler at its Awarua site, near Invercargill.

The site’s two coal boilers continue to operate, and the company continues using coal[9]. In the words of the company’s chair, “to be environmentally sustainable, the business must also be economically sustainable”[10].

Fonterra rules out electrification

The big cheese, Fonterra, has in the past investigated the economics of electrification of its boilers namely at one of its largest South Island plants, Edendale, and a small Otago cheese factory, Stirling.

Its electrification feasibility study at Edendale found that electrification would have increased the site’s operating expenses by about 50%[11] and required investment in electrical infrastructure of about $160,000,000[12].

At a much smaller scale, Fonterra looked at electrifying the process heat at its Stirling site – a cheese factory near Balclutha, in Otago[13].

After some analysis, Fonterra decided against electrifying boilers at Stirling, or any of its sites[14]. This is because even though significant emissions reductions can be achieved, the upfront and ongoing costs are too high[15].

The red meat sector

In 2020 meat processors around New Zealand consumed about 95,000 tonnes of coal[16], which accounts for about a third of the sector’s energy supply[17] (the remainder coming from natural gas, and a small amount from wood, LPG, and diesel).

Meat company, ANZCO, has stated the upfront cost of electrifying its boilers to run on electricity would be about $41,300,000[18].

The company has previously listed its energy costs at $5,320,000 per year – if electricity were used instead, this would go to $16,500,000 – an increase of 210%.[19]

Given about 20% of ANZCO’s operating expenses are spent on energy already, such a substantial increase in energy bills would increase the company’s total operating expenses by 42%[20] – a lot to take on in what the company calls “a low margin business”[21].

The Meat Industry Association has said the government doesn’t appreciate the enormous challenge of shifting what will probably be “some mix of electric heat pumps and biomass”[22], and but that the likely cost could be “an excessive burden on an industry already facing significant headwinds”[23].

It has also said the national electrical reticulation is not capable of meeting the demand for large electrically heated boilers, which will require significant construction of new electricity networks, and there will be difficulties in connecting sites moving to electrical heating by 2030[24].

The Meat Industry Association has said heat pumping, using the refrigeration plant as a heat supply, would be the most efficient method, and could reduce demand by a further 25%, but that this would be an extremely costly option. The Meat Industry Association says once heat pumps are installed, the remaining thermal demand is modest and should be able to be supplied by smaller bio-mass boilers[25].

Silver Fern Farms announced this year plans to reduce its coal use by 50% by 2023[26] through the installation of heat pumps at its Finegand plant in Balclutha, and Belfast, near Christchurch. The total cost of these installations has been put at $7,640,000[27], half of which has been paid for with government funding.

The company plans to reduce coal use by two-thirds by 2025 and eliminate the use of coal at its plants by 2030, through using biomass in favour of coal[28].

Only time will tell the extent to which meat companies can partially or fully electrify their plants, in conjunction with biomass (the supply of which remains uncertain) and when technology will reach such a point that it can be done cost-effectively.

Vegetable growers

For those who grow fresh vegetables in hothouses all year round, energy largely comes from fossil fuels, geothermal, and to a lesser extent biomass and waste oil. Horticulture NZ says the energy profile of the sector is “natural gas where there is access to it in the North Island, and predominately coal in the South Island”[29].

Some growers have investigated electricity as an alternative, but being rurally located and needing significant energy, the power companies cannot supply the amount of electricity that would be required due to transmission constraints. It is also cost prohibitive as a fuel source – for example, a South Island based greenhouse grower advised conversion to electricity would triple their energy cost[30].

Of the estimated 256 hectares of New Zealand where crops are grown under cover, one small grower among respondents to an industry survey is using electricity to heat their glasshouse[31].

Horticulture New Zealand has said electricity currently does not compare well with other fuel options on a cost per unit of energy basis for heating greenhouses, with electricity prices just too high to be cost effective[32].

Scaling up electricity generation and distribution at a national scale

State owned enterprise, Transpower New Zealand, owns New Zealand’s national grid. Transpower estimates New Zealand’s electricity generation will need to increase by almost 70%[33] (and potentially up to 100%) if the country is to electrify process heat, the vehicle fleet, and meet the needs of a growing population.

Transpower’s analysis on this topic doesn’t specify how electricity prices will be reduced to the extent that electrification becomes a cost-effective alternative to natural gas or coal for large industrial energy users in New Zealand.

Summing up

While there is likely to be further improvement in heat pump and electrode boiler technology, and an increase in electricity supply over time, it is not possible to determine when – or if – electricity will become a competitive alternative to fossil fuels for New Zealand’s dairy, meat, and vegetable producers.

Hospitals, schools, and other public institutions can electrify some heating processes, but at a higher ongoing running cost than through coal use.

New Zealand Steel cannot use electricity for manufacturing steel from raw materials because carbon is required as a chemical ingredient.

While growing New Zealand’s electricity supply and infrastructure is a big part of the equation, at 3-5 times the price of coal and gas, electricity has a place in supplementing and reducing fossil fuel use, but with today’s technology and at today’s prices, it’s simply too expensive.

References

View the references page for this article here.