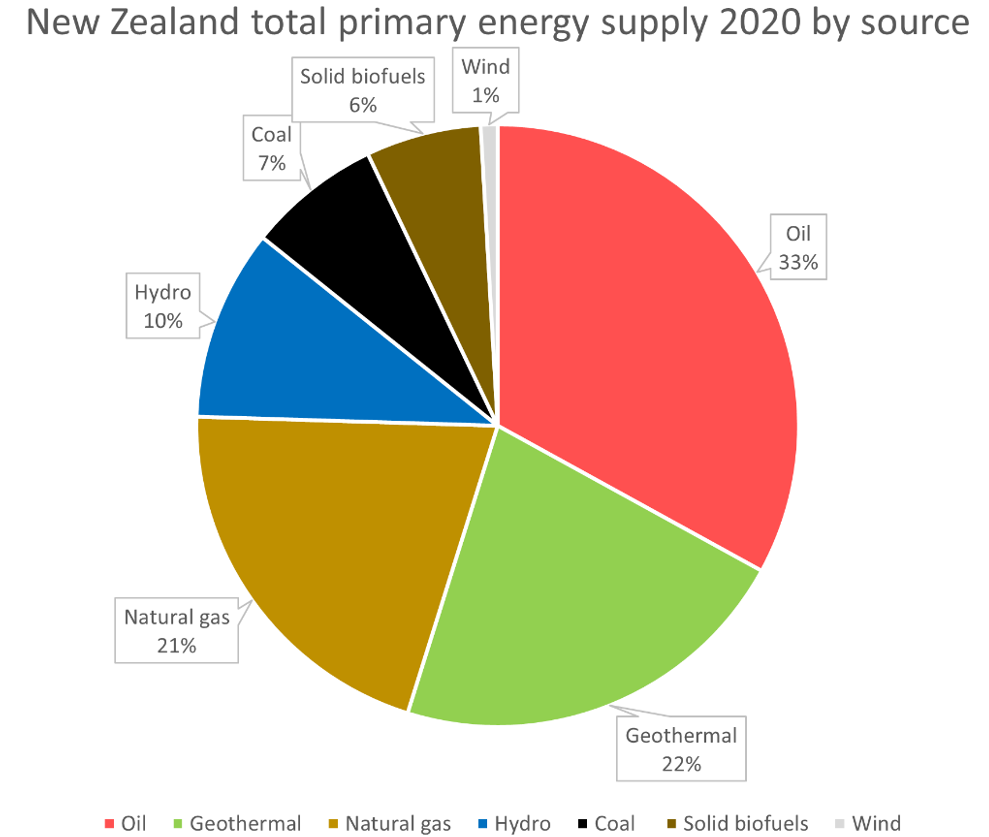

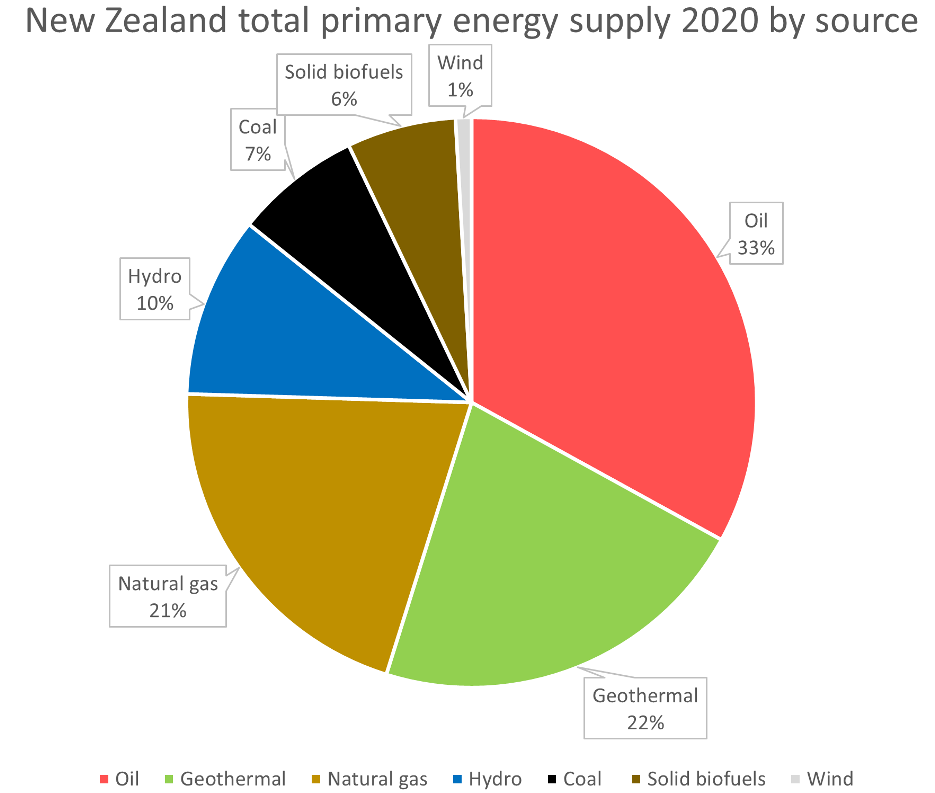

New Zealand uses a fair bit of energy. The majority of this energy doesn’t come from coal – in 2020, coal made up about 7% of New Zealand’s primary energy supply[1] (not to be confused with electricity).

In fact, the largest source of energy is oil (largely in the form of petrol and diesel) for moving people and goods around the country and the world. Coal is actually well down the list from oil, and other heavy hitters like geothermal, natural gas, and hydro.

The below graph shows the percentage of New Zealand’s total energy supply by source in the most recent year for which data is available – 2020[2]. Energy sources not shown on the graph include biogas, waste heat, solar, and liquid biofuels – combined these energy sources accounted for 0.64% of the country’s energy supply[3].

Outside of producing materials like steel and cement, and generating electricity, the majority of coal burnt in New Zealand is to provide energy for the factories that we use to feed ourselves and the world (and pay the bills), and then to a lesser extent for warming schools, hospitals, and universities.

Some people think a good way of putting New Zealand’s coal use on the back burner would be to just burn wood instead – but just how simple is it to make this switch?

Wood supply in total

Coal accounted for about 7% of new Zealand’s energy supply in 2020. The use of coal varies mainly due to the changing needs of the electricity sector – for example when renewable electricity generation hit a 35 year high in 2016, coal accounted for only 5.7% of energy supply[4] (52PJ) versus last year’s 7% (64PJ).

In 2020, New Zealand used about 48 PJ of solid wood fuels[5], largely in the wood processing sector where offcuts and waste wood are used as a readily available energy source in boilers[6].

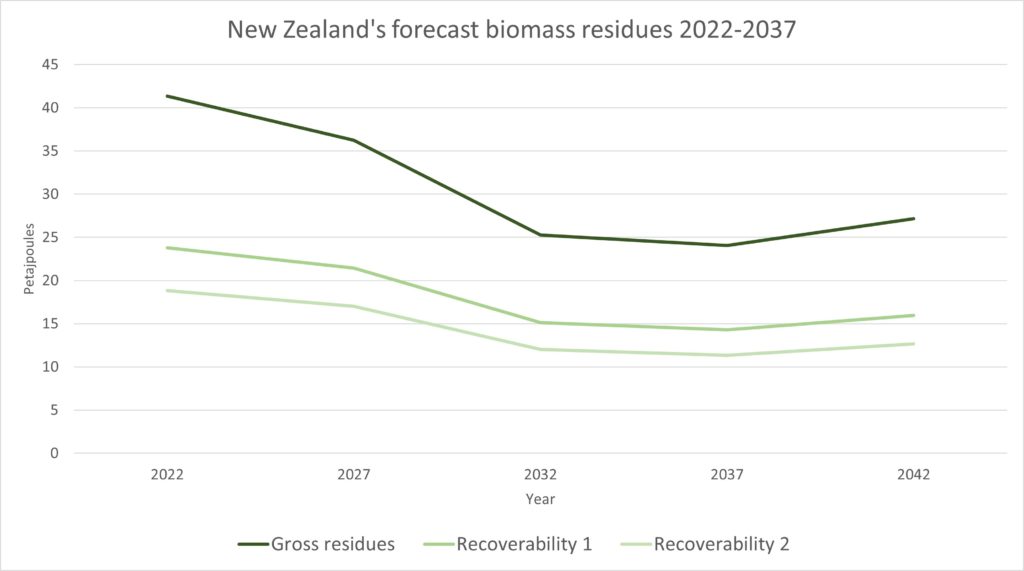

In 2017 Scion, a Crown funded research institute for the forestry sector, looked into the energy potential of New Zealand’s residual biomass that has not yet been realised. This did not include the wood fuels already being used that account for the 5% of the country’s energy supply.

The largest source of biomass likely to be available is from forestry sites after log harvesting has been completed – these can be taken form roadsides and landings, and cutover areas where bark, branches, and stems are left behind.

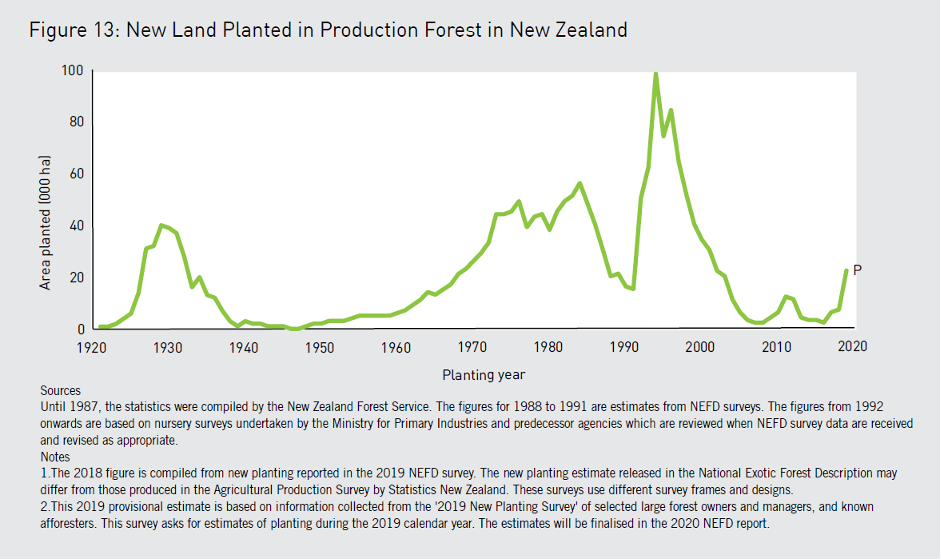

Scion’s forecasts indicate the availability of in forest wood residues will begin to fall from 2022 onward[7]. The graph below is based on data compiled by Scion in 2017.

The gross (or total) biomass available will not all be economically or technically recoverable or desirable. As such, Scion set out two different recoverability levels when it carried out the analysis.

This forecast fall in the recoverable in forest residues is a result of the planting boom that took place through the 1990s. As is shown in the below graph (sourced from a forestry document compiled by the Ministry for Primary Industries) planting peaked at 98,000 hectares of new plantings in 1994, and fell to as low as 2,000 hectares in the mid-2000s[8].

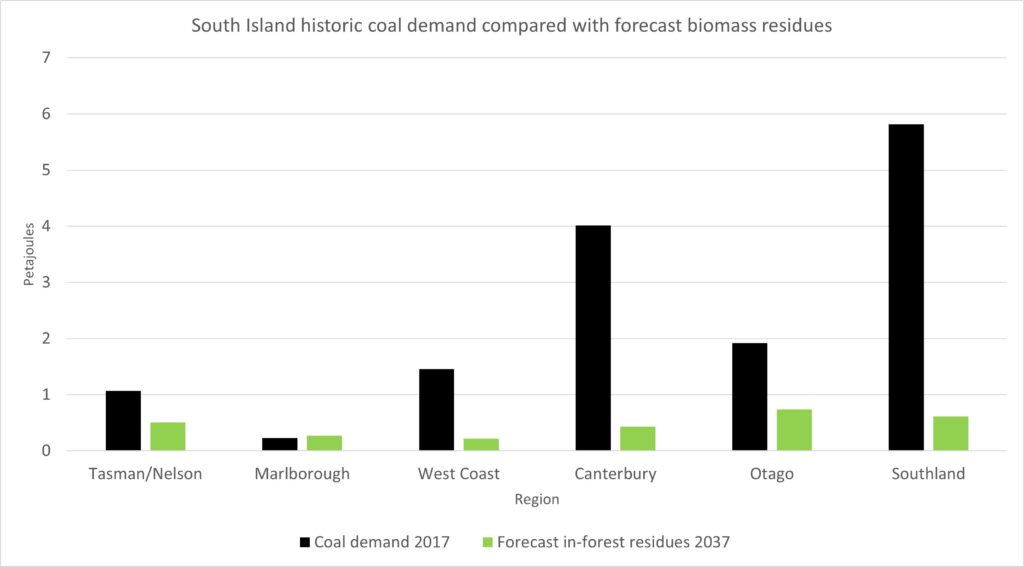

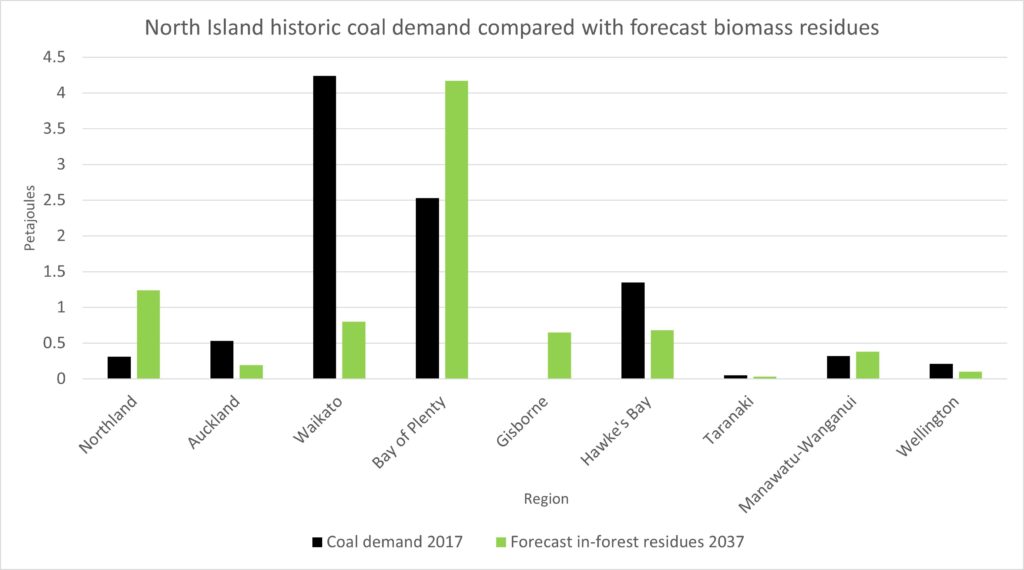

The above graphs only give a picture at a national level. Of greater significance is the heavy regional concentration of New Zealand’s exotic forestry plantations. Much of the residual wood supplies will likely be beyond the economic range of current coal users.

All but one region in the South Island has a demand for coal far in excess of the forecast in-forest residues[9]. The amount of wood available in 2022 is as high as it will be in the next 20 years.

There are areas of the North Island with comparatively abundant wood residues, but in areas with little coal to displace.

The above two graphs do not include the coal demand from electricity generation and steel production.

Due to the ongoing cost of electricity being so high (3-5 times the current price of coal or natural gas [10] ) most industrial coal users have identified some form of wood fuels as the most likely energy source as an alternative to coal.

Assuming wood based fuels were technically viable as an alternative to coal, the big question would be around price.

In its analysis, Scion noted that the first users to contract supply for biomass residues are likely to get the cheapest and best quality resource[11] – those who follow may find the cost rises and the resource quality deteriorates.

Those in the business of processing dairy products and red meat, and growing vegetables in hothouses have all previously expressed to the government concerns about the regional availability of wood residues as opposed to coal, and/or the likelihood that as demand for wood fuels grows (but supply is static or falling) the cost of wood fuels is likely to increase.

Who’s using wood fuels already?

As the above graph shows, New Zealand’s already burning a fair bit of solid biofuels – or in English, wood. About 90% (or more) of all the wood burnt as fuel in New Zealand is used in wood processing[12] – milling logs, dressing timber, making plywood, and pulp and paper manufacturing for things like supermarket bags and stationery for schools.

Unsurprisingly, a place that cuts up wood probably has an easy time finding wood to burn to run boilers to raise steam – plus, they’ve got to get rid of it somehow.

Outside the wood sector?

The biggest coal and gas users in the country are in the business of generating electricity, manufacturing steel and cement, and producing and processing food.

Almost everyone using coal today would love to stop tomorrow (if not yesterday) if they could still run a business after switching to something else.

Wood’s being looked to (along with electricity) as a post-fossil fuel.

Fuelling Fonterra’s fires

Fonterra, the great big dairy cooperative that turns over about $20,000,000,000 per year, has a list of public relations headaches, and fairly well near the top is being one of New Zealand’s largest coal users.

Following assessments of two sites in the South Island that have until now run on coal, Fonterra has ruled out electrifying any of its sites due to the cost – it’s simply too expensive[13].

That leaves wood, which is being used (or will be very soon) at three of Fonterra’s sites around New Zealand.

Brightwater

The first of these is the company’s Brightwater site, a small factory operating just south of Nelson. In 2018 the plant began ‘co-firing’ coal with wood, reducing the site’s carbon dioxide emissions by 25% – meaning its coal use has dropped about a quarter, and 75% of the energy the site needs is still supplied by coal[14].

Brightwater is a small plant – it accounts for all of 1.7% of Fonterra’s South Island energy use[15].

On top of being small, it’s literally across the road from its wood supplier, Azwood[16]. Most coal users raise concerns about the transport and storage difficulties with wood versus coal (on average, 3-4 truckloads of wood are needed to match the energy of one truckload of coal), but with this plant, no such issue exists.

Nonetheless, Fonterra, for reasons only known to people within the company, continues to burn coal at Brightwater, despite it being the second smallest of its South Island plants and its proximity to its wood supplier.

It would be fair to assume that if Fonterra could run the plant on wood, and wood alone, that’s precisely what it would do – the only reason that the site continues to burn coal must be because that’s the only way the site can continue to run. Otherwise, it must be because Fonterra just likes burning coal, which isn’t likely given the company’s many public commitments to ending its coal use as soon as possible.

Te Awamutu

At the cooperative’s much larger Te Awamutu site – which is a significant energy user – coal use has stopped entirely with the uptake of using wood pellets in place of coal[17]. This is a success story for this particular site, allowing Fonterra to reduce its coal use by about 10%, and reduce emissions by over 80,000 tonnes of CO2 a year[18].

The combination of circumstances that allowed this to occur are not easily replicated. As with all fuels, wood has an economic range – as Fonterra has said, there is a challenge in “ensuring that biomass is located close to where it is required, as distance from source to site can add significant costs.”[19]

In Te Awamutu’s case, of all the factories in Fonterra’s ownership, it’s the closest to the central North Island – the mother lode of forestry. About 72.5% of all the country’s exotic forests are in the North Island, and a third alone are in the central North Island[20].

Nature’s Flame produces wood pellets in Taupo. Wood pellets, are, in the company’s words, “compressed parcels of saw dust” that have only 5-10% moisture[21], burning longer, hotter, and more efficiently than firewood or woodchips – which can have a moisture content of anywhere from 25-80%[22].

Nature’s Flame’s ability to supply large quantities of wood pellets has increased in recent years, due to the company’s use of cheap geothermal energy supplied by Contact Energy[23].

Prior to this arrangement (which began in 2019) the company was burning wood to dry wood and operating at only 45% capacity[24]. With “used” geothermal fluid (already used by a nearby sawmill) being put to use to dry pellets, the company now produces 85,000 tonnes of pellets per year[25] – Te Awamutu alone consumes almost 50,000 tonnes[26].

That this factory enjoys the good fortune that these particular circumstances allow for conversion from coal to wood pellets shows how hard it will be for any of the cooperative’s South Island factories to convert away from coal.

In the South Island coal use is significantly greater, wood residues are significantly scarcer, and geothermal is non-existent as a commercialised source of energy.

It’s also worth noting that while this has ended the company’s use of coal at Te Awamutu, the factory continues to burn natural gas, meaning that its use of fossil fuels has reduced significantly, but not ended.

Stirling

Fonterra’s latest cab off the rank for fuel-switching is its Stirling Plant, which will be running on wood fuels by August 2022[27]. Fonterra’s Stirling factory produces cheese, not milk powder – the process is less energy intensive, so a conversion of this site is easier than larger sites that dry milk powder.

Wood residues, while not as abundant as the North Island, are available in large enough quantities in Otago to meet the needs of the small cheese factory, and will be supplied by Pioneer Energy, a wood fuel supplier.

Because Brightwater still uses coal and Te Awamutu still uses gas, this will be the cooperative’s first fully renewable plant – albeit at a plant that accounts for about 2.6% of Fonterra’s energy needs in the South Island and 0.8% at a national level[28].

Use of biomass as a replacement for fossil fuels in the hothouse sector

The horticultural sector has said that for converting away from coal and natural gas for heating hothouses, wood fuels are the most likely alternative source of energy. One issue that has consistently been raised however, has been the reliability of supply of wood fuels, and the distance they may need to be transported.

One large grower in the Nelson region, JS Ewers, is switching to wood fuels with government assistance.

JS Ewers has been able to draw on comparatively available wood resources from the Nelson area. Prior to the government support being granted, JS Ewers had taken steps to cut its energy consumption and reduced from eight operational coal boilers to three[29].

The company investigated installing its own solar generation or electrification and found neither option was feasible[30]. The company instead chose to convert its remaining coal capacity to biomass with government funding. The company has also said biomass supply needs to be sourced from within 100 kilometres[31].

The extent to which this can be replicated by other growers remains unknown. One grower in the North Island, near Auckland, looked at converting from natural gas to woodchip. The grower said this would require 10 – 13 truck and trailer loads of woodchip a day and significant storage capacity[32].

The grower said this was easy to do by buying a woodchipper and chipping the slash from forestry areas and using truck and trailers for transport. This grower said another large grower had the same idea, and after talking the pair found they were competing in the same forestry catchment – the issue being that “within no time, we would clean that area up with supply becoming a problem after a few years…both parties agreed there is not enough woodchip in the Auckland area, and this is not a preferred option”.[33]

Takeaway points

The first question to answer is whether New Zealand has enough wood residues, in terms of energy, to allow for wholesale substitution of coal at a national level – the answer to that question is no.

The next question is whether some regions have enough forest residues and wood processing waste to replace coal, and in the case of the South Island (and areas of the North), the answer is also no.

That converting from coal to woodchip and wood pellets will work for some coal users in some areas is true – that doesn’t mean it is a solution for every coal user everywhere. With Nature’s Flame producing about 85,000 tonnes of pellets a year, and one Fonterra factory chewing through 50,000, this avenue will obviously have its limits.

Where available, undried wood fuels seem capable of replacing coal in space heating (schools, hospitals, hothouses) and for less energy intensive processes like cheese making.

In terms of wood fuels reducing the size of coal’s slice in the New Zealand energy supply pie (graph repeated below), whether it can do so by much more than a smidgen, or a sliver remains to be seen.

References

View the references page for this article here.