How much fossil fuel is in New Zealand’s food?

When it comes to great, home grown food New Zealand is a proverbial land of plenty. Even if we grumble about the price of our supermarket bills – the availability of a wide range of quality food is never in doubt in this country.

Ask most kiwis about where our food comes from, and many would conjure up images of pin straight rows of crops sprouting from fertile soils, sheep grazing lazily on rolling hillsides, and piebald cattle grazing through fields of clover. Or something like that.

But these scene are very much ‘stage one’ of food production. Getting all that fodder to the country’s collective tables requires a long production chain.

And that chain requires a lot of energy.

Much of that energy, currently at least, comes from fossil fuels. Natural gas and coal are heating our hot houses, burning in our milk boilers, and powering our meat processors.

With moves afoot to get rid of coal, and increasingly uncertain supplies of natural gas, it’s worth considering just how reliant we are on these fuels. And what price we will have to pay if we rush into a future of fossil fuel-free food.

A fresh look at our produce

What do our local tomatoes, cucumbers, capsicums, eggplants, chillies, and lettuce have in common? Besides being perennial Kiwi favourites, all these vegetables are grown in hothouses.

These hothouses are heated with boilers to ensure a constant temperature twenty four hours a day, twelve months a year, to keep things growing[1].

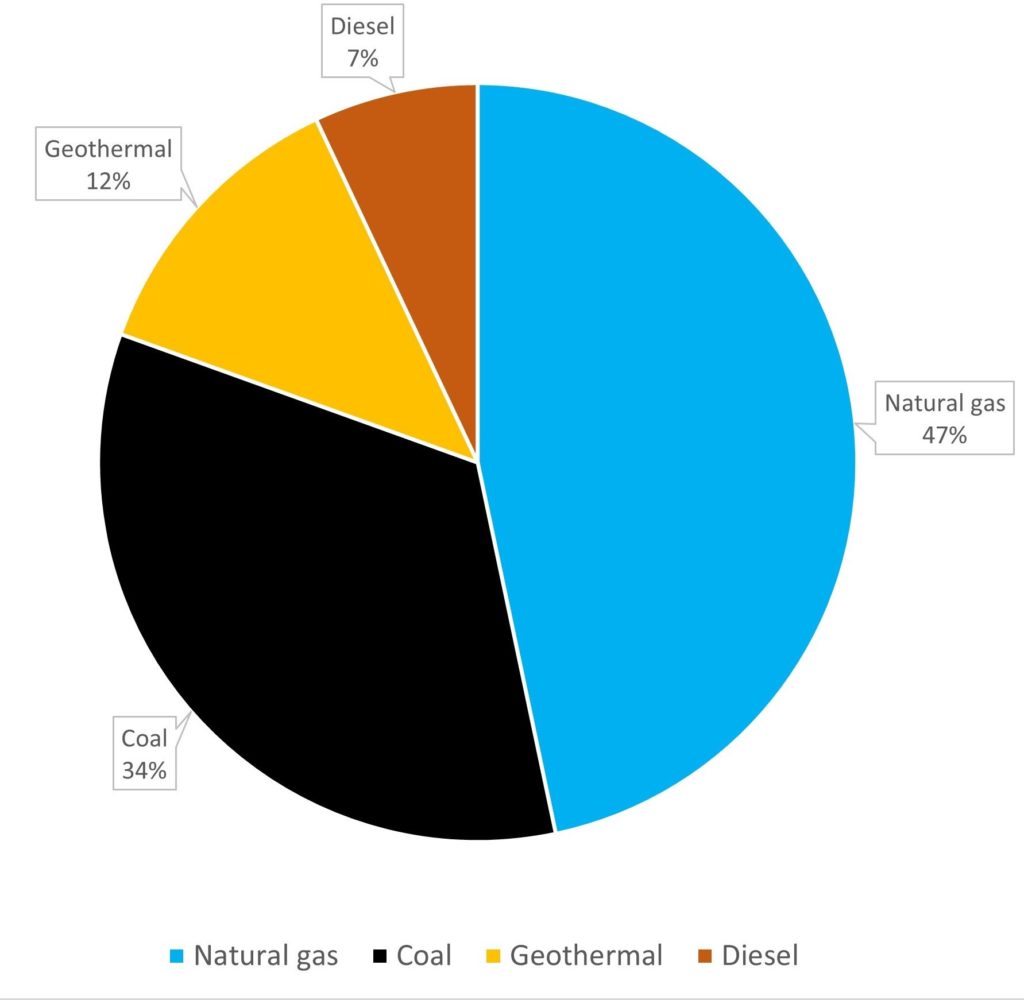

As an industry, hothouse vegetable growers around New Zealand get almost half their energy from natural gas, a third from coal, an eighth from geothermal energy, and a little bit from diesel[2].

Where natural gas is available, like in the North Island, it tends to be used. In remote areas – like the entire South Island – coal tends to be the go to fuel.

Coal is the sector’s second largest energy source, with about a third of all energy used in the hothouse sector coming from this fuel.

Could government polices mean an end to the supply of fresh, New Zealand grown vegetables?

The industry has told the government the impact of phasing out existing coal boilers would be devastating for growing vegetables and in turn supply of fresh vegetables – particularly in the South Island[3].

Growers have warned the government some businesses have already closed down as a direct result of the price of units in the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme making the cost of coal uneconomic and having no alternative economic energy source to turn to[4].

Surely there are alternatives to coal and natural gas?

The government is proposing to ban new coal fired boilers with temperature requirements below 300°C, and phase out existing coal boilers within the same category within 16 years.

The horticultural sector has made it plain for those growers relying on coal, there is no viable alternative currently available[5].

Many local growers admit they cannot afford to transition to the proposed alternatives like electricity and biomass.

Does that mean no fresh produce?

Horticulture New Zealand has said most likely any fall in domestic production would only be able to be offset with imports[6]. These imported vegetables would have to come in by air-freight, with a much higher carbon-footprint.

Some Australian grown vegetables are already imported into New Zealand to supplement domestic production (usually for seasonal and climatic reasons). These Australian hothouses also use coal, gas, and diesel, but production is not subject to carbon-pricing or an emissions trading scheme as it is in New Zealand.

Basically, if New Zealand hothouse production becomes unviable due to the phasing out of fossil fuels, there would almost certainly be increased imports from Australia[7] – where growers use fossil fuels.

Get to the meaty bit

On a trip through the supermarket, nine out of ten Kiwis will stop by the meat section. Before a sheep or cow ends up on a barbecue or in an oven, it takes a journey from the paddock, via a stock truck, through your friendly neighbourhood freezing works, and out the other end as a supermarket special.

The plants that process and package our local meat require a large amount of energy. This largely comes from (you guessed it) fossil fuels.

About 61% of energy used in meat processing is sourced from natural gas, 31% is coal, and the remainder is a mix of LPG, fuel oil, and wood (8%)[8].

The majority of the coal use (80%) is in the South Island where natural gas simply isn’t an option[9].

About 95,000 tonnes of New Zealand’s coal went into meat production in 2020[10].

Surely there are alternatives to coal and natural gas?

A group representing the red meat sector has told the New Zealand government while producers of beef and lamb support moving from coal to electricity and biomass, there are enormous challenges in doing so.

It says continuing to operate while adopting “relatively new and untested” technology in will likely cost up to $80,000,000 is an excessive burden for an already struggling sector[11].

It says in many areas of the South Island (where coal is used) there is simply not enough biomass to make a conversion viable. And electricity is just too expensive.

If the energy bills for meat processing companies increase due to phasing out fossil fuels, it’s not hard to imagine that these costs will be passed on to the consumer.

Let’s pop to the Dairy

Whether it’s milk in your morning brew, butter on your midday sandwich, or cheese on everything we can possibly put it on, most of us have a bit of dairy in our diet.

Milk goes through all sorts of processes to end up as creamy, cheesy, buttery commodities – and yes, these processes require a fair bit of energy.

And yes, once again, much of that energy comes from fossil fuels.

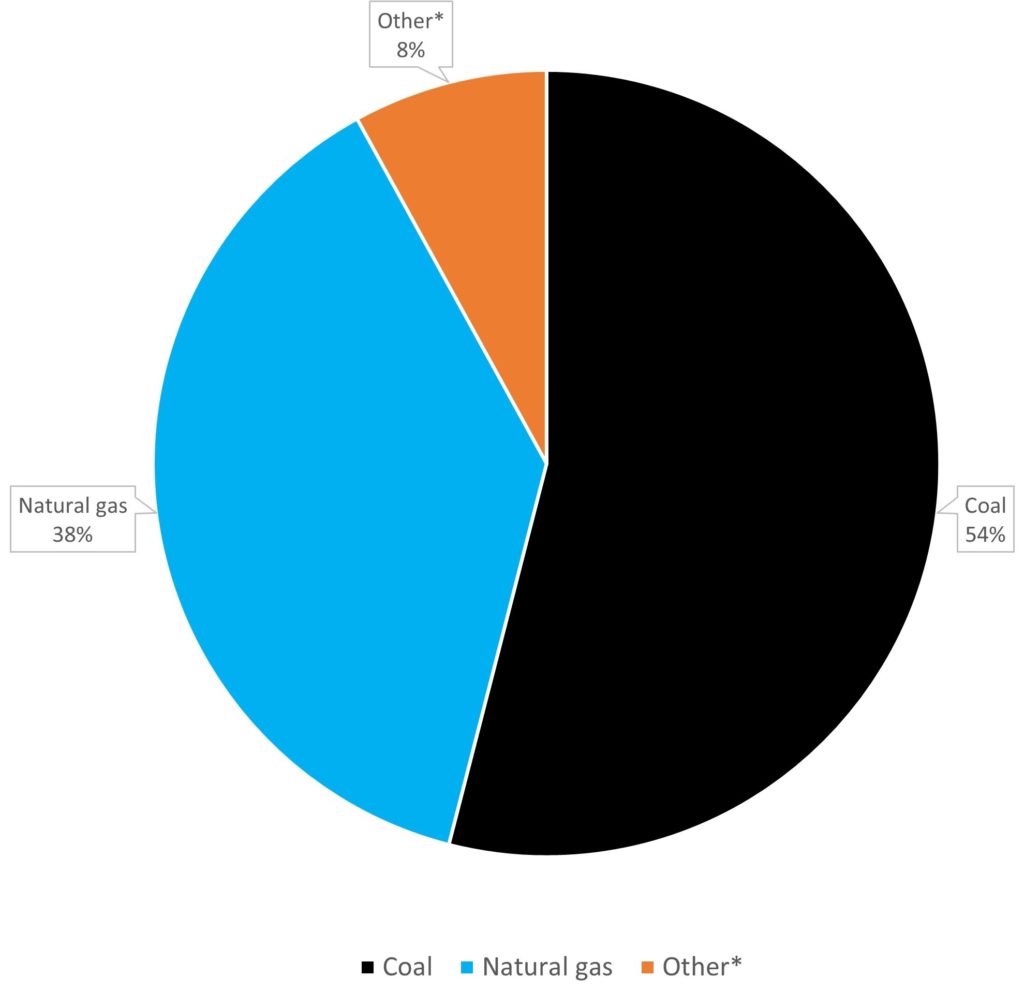

Milk processing and manufacturing gets a touch over half of its energy from coal, close to 40% from natural gas, and the balance from diesel, LPG, fuel oil, and geothermal[12].

Surely there are alternatives to coal and natural gas?

You might be surprised to hear that nobody is burning coal for the kudos. The dairy industry, as with all the other food producing industries, would love to stop using coal if they could afford to.

In 2018 Fonterra announced Stirling, a south Otago cheese factory, would switch from coal to electricity. After a closer look, due to investment required and an increase in the day-to-day cost for the cooperative, not only will Stirling not be switching to electricity, but none of the cooperative’s factories will be[13].

New Zealand’s largest meat company, Silver Fern Farms, has announced it will be ending coal use by 2030 – but the technology to achieve this remains unproven. Other meat companies, such as ANZCO, have said operating in ‘such a low margin business’[14], its key concerns are coal-alternatives are not readily available, or conversion and ongoing costs are just ‘too high’.

Vegetable growers have said electricity simply isn’t feasible for heating hot houses due to the high cost[15].

The only other option open to coal users is to switch to wood-based fuels. The main issue is whether there’s enough to go around. And there doesn’t appear to be.

The majority of coal use (excluding electricity generation, steel, and cement production) is in the South Island. Most of the country’s plantation forest (72.5%) is in the North Island[16]. Freighting that wood residue long distances is not considered economic[17].

So, coal-fuelled Kiwi food… forever?

No. But for now, and for the foreseeable future, coal will have to be a part of food production in New Zealand.

Keeping food at affordable prices for those of us who eat it (as well as being competitive against imported products here and competitors in export markets) means making sure the energy sources we use don’t significantly increase the cost of production. Until an alternative energy source becomes more cost-effective, new technology is developed, or we become capable and willing to pay more for what we eat, we will rely on coal and natural gas to help New Zealand feed itself.

References

View the food references page here.